What to Give Baby if They Have Chorioamnionitis

- Research article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Direction of Belatedly Preterm and Term Neonates exposed to maternal Chorioamnionitis

BMC Pediatrics volume xix, Article number:282 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Chorioamnionitis is a significant run a risk factor for early on-onset neonatal sepsis. However, empiric antibiotic treatment is unnecessary for almost asymptomatic newborns exposed to maternal chorioamnionitis (MC). The purpose of this study is to written report the outcomes of asymptomatic neonates ≥35 weeks gestational historic period (GA) exposed to MC, who were managed without routine antibody administration and were clinically monitored while post-obit complete blood jail cell counts (CBCs).

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed on neonates with GA ≥ 35 weeks with MC during agenda yr 2013. Information technology ratio (young: total neutrophils) was considered suspicious if ≥0.iii. The information were analyzed using independent sample T-tests.

Results

Amid the 275 neonates with MC, 36 received antibiotics for possible sepsis. Twenty-one were treated with antibiotics for > 48 h for clinical signs of infection; merely one babe had a positive blood culture. All 21 became symptomatic prior to initiating antibiotics. Six showed worsening of IT ratio. Thus empiric antibody administration was safely avoided in 87% of neonates with MC. 81.5% of the neonates had follow-up appointments inside a few days and at two weeks of age within the infirmary system. At that place were no readmissions for suspected sepsis.

Conclusions

In our patient population, using CBC indices and clinical observation to predict sepsis in neonates with MC appears prophylactic and avoids the unnecessary use of antibiotics.

Background

Chorioamnionitis or intraamniotic infection is defined as acute inflammation of the membranes and chorion of the placenta, typically due to ascending polymicrobial bacterial infection. Near unremarkably, chorioamnionitis is associated with ruptured membranes, but organisms including Group B streptococcus, Ureaplasma species, Mycoplasma hominis, and Listeria monocytogenes infect intact membranes as well. MC is a significant run a risk factor for early on-onset sepsis (EOS) due to Group B streptococcus (GBS) and can reverberate an intrauterine onset of infection in the neonate [i, 2]. The traditional diagnostic criteria for clinical chorioamnionitis include maternal fever (> 100.4 °F persisting more than one h or whatsoever fever more than 101 °F), and two or more than of the following: fetal tachycardia (> 160/min), maternal tachycardia (> 100/min), uterine tenderness, and foul-smelling or purulent amniotic fluid.

To address possible EOS in asymptomatic newborns with MC, the 2010 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Center for Illness Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend a limited evaluation including claret civilisation (at nascency) and CBC with differential (at nascence and/or at six–12 h of life (HOL) forth with initiation of empiric antibiotics. Still, a contempo epidemiological study found that among term infants exposed to MC, just xiii.5% received antibiotics after nascency [3]. This deviation from guidelines, equally seen in practise, has been attributed to improved obstetrical interventions, which significantly decreased the risk of sepsis in late preterm and term neonates in this setting [4]. A multispecialty workshop sponsored past the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, recommended treating late preterm and term neonates only if the diagnosis of chorioamnionitis is confirmed with pathology or microbiology [5]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supported this and introduced the term intraamniotic infection for chorioamnionitis. They further defined suspected intraamniotic infection as maternal intrapartum fever (single maternal temperature ≥ 39.0 °C or a temperature of 38.0 °C–38.9 °C that persists for > 30 min during labor) presenting with 1 or more of the post-obit: purulent cervical drainage, maternal leukocytosis, and fetal tachycardia [6]. The most contempo AAP argument addressing management of neonates born at ≥35 weeks GA at hazard for EOS suggests utilizing a locally tailored guideline by nascence centers, for EOS run a risk assessment and clinical management [7]. They also suggested utilizing multivariate risk assessment tools like the Neonatal Early Onset Sepsis Risk Calculator to appraise the take a chance of EOS [7,8,nine]. In our hospital, the practise is to perform CBCs at 6 and 24 h afterward birth, and initiate the sepsis work-up and antibiotics (Ampicillin and Gentamicin) only if the infant develops signs/symptoms of sepsis or the CBCs suggest infection. Since our practise was initiated, others accept looked at the management of neonates exposed to MC without antibiotics [10, 11]. The purpose of this study is to study our observational do of managing asymptomatic neonates ≥35 weeks GA exposed to MC without empiric antibiotic administration. In addition, we include follow-up of these neonates after hospital discharge to evaluate the safety of our practise.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was done on all neonates with GA ≥ 35 weeks, who were exposed to MC. The study included 275 neonates over 12 months (January to December 2013). The institutional review board at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston canonical this study. In November 2012, we instituted a do guideline for management of asymptomatic neonates exposed to maternal chorioamnionitis, using series CBCs and close ascertainment. For the study, MC was defined as maternal treatment with antibiotics for chorioamnionitis. Data collected included the following:

-

Neonatal demographic data included birth weight, gender, and gestational age.

-

Maternal data including maternal historic period, GBS condition and antibiotic treatment before delivery.

-

Results of CBC with differential at six and 24 HOL, including the ratio of immature to mature neutrophils (I/T ratio), absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and total leukocyte count (TLC). The differential count is obtained manually by trained technicians and confirmed past hematologists. I/T ratio was considered suspicious if ≥0.3.

-

Presence of signs and symptoms of sepsis including respiratory distress (tachypnea: respiratory rate > sixty/min, increased work of breathing or need for oxygen), temperature instability (Temperature < 36.five C that could non exist attributed to environmental factors), hypoglycemia and feeding difficulty (poor feeding with low urine output).

-

The incidence of sepsis work-upward and transfer to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

-

Results of blood culture and time interval for information technology, organisms isolated, length of antibody use and hospital stay.

-

Nautical chart review for follow up visit 2–iii days after discharge and at two weeks of age.

-

Nautical chart review for readmission after discharge to rule out sepsis.

The information collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and independent sample T-tests. SPSS software platform was utilized to do the statistical assay. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2013, 5006 babies ≥35 weeks gestation were born at UTMB. Two hundred 70-five were born to mothers with a diagnosis of chorioamnionitis, for an incidence of 5.49%. At least two CBCs were obtained on all neonates with MC. The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Tabular array 1. 1 hundred sixty (58.2%) of the infants were born via vaginal delivery. Of the 275 mothers with chorioamnionitis, the majority were non colonized with GBS. Of those who were positive for GBS, xc% were treated fairly. Tabular array ii illustrates the GBS status of the mothers and the information near their treatment. 68.iv% of the mothers with the diagnosis of MC were administered antibiotics at least one hour before delivery.

The showtime CBC was obtained at a mean of 5.85 HOL (range 0–12, manner 6). The mean ANC was 14.9 ± v.five, and the hateful I/T ratio was 0.29 ± 0.xv at this fourth dimension. I hundred sixty-three infants (40.7%) had a suspicious I/T ratio (> 0.three) on the first CBC. Simply 1 out of the 163 infants with increased I/T ratio at the time of first CBC was diagnosed with EOS with a positive blood civilization. The positive predictive value (PPV) for early on I/T ratio (> 0.3) to diagnose EOS was 0.61%(95% CI 0.56–0.68%). The second CBC was obtained at a mean of 22 HOL (range vii–32, mode 24). Hateful ANC was 12.16 ± 4.8 and mean I/T ratio 0.18 ± 0.15. Fewer infants (xviii.54%) had a suspicious I/T ratio on the second CBC. The PPV of I/T ratio (> 0.iii) to diagnose EOS at the time of the second CBC was 1.96% (95% CI ane.53–2.51%). In 48 infants the I/T ratio increased at the time of second CBC. This increment in It ratio was non predictive of change in clinical presentation every bit simply 6 out of these 48 infants had clinical signs of sepsis. Twenty-two of these infants had an initial CBC with I/T ≥ 0.iii.

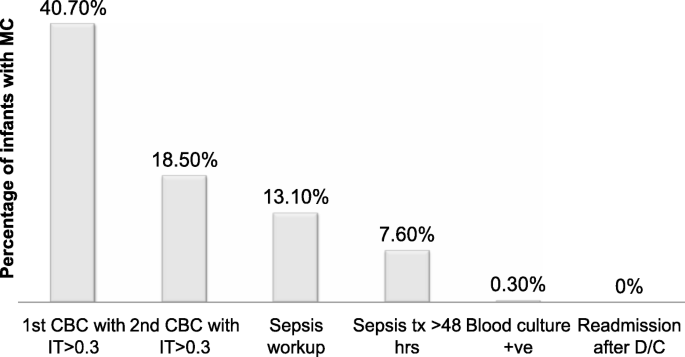

Non all neonates with an increment in I/T ratio were transferred to the NICU for further workup. The decision to transfer was fabricated based on the overall clinical presentation of the infant and attending's judgment. Thirty-6 infants (13.1%) were transferred to the NICU for further evaluation including claret culture and antibiotics. Although only ane infant had a positive blood civilization, 21 infants (vii.6%) were treated with antibiotics for more than 48 h due to concern for clinical sepsis (Fig. 1). The duration of antibiotics in these infants ranged from iii to 7 days and was dependent on clinical judgment of the attending. The infant with a positive blood civilization was born via vaginal delivery at 35 weeks GA and developed respiratory distress within the first 6 h after birth. She was transferred to the NICU due to clinical suspicion for EOS and was found to take a high I/T ratio of 0.72 and 0.48 at the time of the get-go and 2nd CBC, respectively. She was treated with antibiotics for 10 days for civilisation positive sepsis. Babe's mother was diagnosed with MC based on loftier maternal temperature (101 °F) along with fetal and maternal tachycardia. All neonates treated with > 48 h of antibiotics developed clinical signs of sepsis (respiratory distress, poor feeding or hypothermia) and 28% of these neonates had an increase in the I/T ratio. Figure 1 shows the per centum of infants with MC who received further management.

Progression of direction of infants exposed to maternal chorioamnionitis

An independent-sample t-exam was conducted to compare the CBC indices in the neonates who were treated with antibiotics for > 48 h with neonates who were either not treated or treated for ≤48 h (Tabular array 3). Both IT ratios differed between the group treated with antibiotics > 48 h vs. those treated for ≤48 h and untreated group (p = 0.003 for the outset CBC, p = 0.002 for the second CBC). At the time of first CBC, rupture of membrane (ROM) > 18 h was associated with a higher likelihood of a suspicious It ratio (p = 0.023). There were no significant differences with regard to gender, nativity weight, manner of delivery or presence of respiratory distress.

All newborns are scheduled for follow-upwardly appointments at ii–iii days and 2-weeks after discharge. 2 hundred 20-four neonates (81.5%) attended the two–3 days appointment and 226 (82.two%) were seen at two weeks of age at a dispensary within our hospital organisation where a total history and physical exam was obtained. At the time of follow up visits, none of these infants exposed to maternal chorioamnionitis demonstrated any concern for sepsis. Furthermore, none of the infants in our study were readmitted to our infirmary for evaluation of sepsis.

Discussion

Maternal chorioamnionitis is a well-known hazard factor for EOS; however, there is considerable variation in the accepted definition and diagnosis of MC. Oftentimes it is used to describe a heterogeneous group of conditions ranging from sterile inflammation to infection of varying degree of severity and duration. Some centers diagnose MC past the presence of intrapartum fever alone (unexplained by other infection), while others favor a diagnosis described by Gibbs et al. [12] that requires presence of intrapartum fever of at least 100 °F (37.eight °C) besides equally at least 2 additional clinical signs (maternal tachycardia > 100 beats per minute, fetal tachycardia ≥ 160 beats per minute), uterine tenderness, foul-smelling amniotic fluid, and leukocytosis ≥ 15,000 cells/mm3) [thirteen]. There are other variations of this definition also in use, and hence the term chorioamnionitis does not consistently reflect the severity of maternal and fetal illness [xiv]. In our setting, the obstetricians assess the adventure for chorioamnionitis using the clinical criteria proposed by Gibbs et al. described above. Antibiotics are begun merely if they make the clinical diagnosis. Our setting is unusual in that the obstetricians (all in the academic maternal-fetal medicine group) accept a unified approach to the diagnosis and handling. The babies born to those mothers are the subject area of this report. We do not have a histological diagnosis for these cases.

The 2010 guidelines past the CDC [15] and AAP [16] recommend treatment of all neonates exposed to MC irrespective of gestational age and presence of symptoms. As a consequence of these guidelines, many term and late preterm neonates are unnecessarily exposed to antimicrobial agents in gild to forbid rare cases of EOS. Surveillance studies approximate the incidence of EOS to be 0.77 cases/thousand live births. This can exist further broken down to ~ 0.5 cases/thou amongst those built-in at ≥37 weeks, compared to ~ 3.0 cases/grand live births occurring at < 37 weeks gestation [17]. However, the presence of chorioamnionitis increases this adventure by 2–iii fold [18]. Reported rates of confirmed EOS in infants built-in at ≥35 weeks' gestation to mothers with clinical chorioamnionitis range from 0.47 to 1.24% [iv, 14]. This take a chance of EOS is reduced if symptomatic newborns are excluded from the analysis [four, nineteen]. In a multicenter, prospective surveillance study EOS was diagnosed in 389 of the 396,586 infants reviewed; lx% of these infants were exposed to MC. The researchers estimated that almost 450 term infants exposed to MC would have to be treated for every case of confirmed EOS [xx]. Despite beingness a relatively small sample size, the information from our study is consistent with the observation that the take a chance of EOS is low in infant exposed to MC (one case of EOS in 275 infants, 0.36%). There were no cases of EOS in infants that were exposed to MC who remained asymptomatic within the offset 24 h. Babies who were < 35 weeks or were clinically ill at birth were admitted direct to the NICU and are not addressed in this report.

A multivariate risk assessment model to predict the risk of EOS, was developed using objective data collected at the time of birth [21] and the evolving newborn condition during the starting time 6 to 12 h after birth [22]. The objective data included the highest maternal intrapartum temperature, the maternal GBS colonization status, the type and duration of intrapartum antibody therapies, the elapsing of ROM and gestational age at the time of delivery. Ane web-based Neonatal Early-Onset Sepsis Take chances Calculator (https://neonatalsepsiscalculator.kaiserpermanente.org) uses a predictive model developed from a large population to calculate the risk guess for EOS and recommend management [23]. The recent AAP statement regarding management of suspected/proven EOS in neonates ≥35 weeks' gestation suggests utilizing the sepsis calculator in conjunction with serial physical exams every 4–6 h for the first 48 h [7]. At our center, nosotros continue to apply series physical exams and clinical assessment to evaluate for take chances of EOS in asymptomatic term infants. Use of multivariate run a risk assessment tool has not been implemented in practice.

In 2016, an Good Panel Workshop summary by the ACOG questioned the current method of diagnosing chorioamnionitis and proposed the use of an alternate diagnosis of Triple I for pathological diagnosis of chorioamnionitis. They further recommended treating tardily preterm and term neonates only if the diagnosis of chorioamnionitis is confirmed with pathology or microbiology. This would involve the presence of clinical symptoms and whatever one of the post-obit:

- one.

Positive gram stain on amniocentesis;

- ii.

Depression glucose or positive amniotic fluid civilization; or

- 3.

Placental pathology revealing infection [five].

Even so, this data is rarely available to use at the time of nascency when the decision to exercise a sepsis workup is being made. In August 2017, the ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice released a committee opinion statement nearly evaluation and management of intrauterine infection [6], which clarified their earlier recommendations and suggested the employ of multivariate risk cess and increased reliance on clinical observation to safely decrease the number of well-appearing term newborns beingness treated empirically with antibiotics. Yet, they did not include Triple I as a new diagnostic category.

Antibiotic therapy in late preterm and term neonates built-in to mothers with MC ideally should be restricted to those who are at increased risk of developing EOS. Unfortunately, no diagnostic test effectively predicts the infants at risk. Hence there are dissimilar approaches used by unlike centers to limit the unnecessary utilise of antibiotics in this setting. Some centers use C-reactive protein in addition to CBC indices to predict the risk of EOS [10, xix, 24] and some utilise the neonatal EOS reckoner to assist with management of these neonates [9, 11]. Most neonates at UTMB are born to mothers who receive prenatal care in a arrangement of Regional Maternal and Children's clinics, which is staffed past members of the OB faculty. Thus, we accept the advantage of large delivery service with a consistent practice of screening for GBS and a standard definition of MC. At our middle, we perform a sepsis evaluation on the footing of CBC indices and presence of other chance factors including duration of rupture of membranes, the severity of maternal illness and maternal GBS colonization.

Historically, CBC indices such as WBC count, ANC, IT ratio and platelet counts have been used to predict the risk of EOS. Hornik et al. studied 166,092 infants and constitute that low WBC count, low ANC, and high IT ratios were associated with increased odds of infection (highest odds ratios: 5.38, 6.84, and 7.97, respectively). They too found that the specificity and negative predictive values of using CBC indices were high (73.vii–99.nine and > 99.8%, respectively). However, sensitivities were depression (0.iii–54.5%) for all complete blood cell count indices analyzed [25]. Based on these results they recommend against the sole use of CBC indices to rule out infection, but to continue monitoring for clinical signs of sepsis and maintaining a high alphabetize of suspicion for those infants at risk remains necessary. Another big retrospective cross-sectional study evaluated CBC indices for predicting the run a risk of sepsis and found that WBC count, ANC and IT ratio were better at discriminating the risk of infection after 4 h of birth as these indices can exist affected by many other factors in the first few hours of nativity [26]. Hence, equally part of our clinical protocol, nosotros obtain the first CBC at virtually six h of life in asymptomatic neonates. In the written report past Hornik et al., elevated I/T ratios (> 0.2, > 0.25, > 0.5) were associated with relatively loftier specificities (73.7, 81.seven, 95.7%, respectively) and negative predictive values (99.2, 99.2, 99.0%, respectively) [25] to predict the risk of EOS. In our study, at the time of first CBC, the lowest value of Information technology ratio was 0.nineteen. The higher Information technology ratio seen in our population may be attributed to inflammatory response associated with chorioamnionitis and frequently associated hazard of prolonged ROM. Our analysis showed that I/T ratio > 0.3 had a poor positive predictive value for diagnosis of EOS (0.61 and 1.96% at the time of the first and second CBC respectively). I/T ratios were not reliably predictive of the perceived need for antibody handling, with a sensitivity of merely 28% for infants with that outcome. Therefore our data supports the recommendation to not use CBC indices lone, to predict the risk of EOS.

Our study has some limitations. First, our sample size was relatively minor. Since the incidence of EOS is relatively low, our study may non be powered to estimate the hazard of not treating the neonates with MC. 2d, clinical sepsis was treated for more than 48 h based on clinical presentation in most cases. Third, our follow up data was limited to 81.six% of neonates in the study, and cannot predict if whatever of those with lack of follow upward within our system were admitted elsewhere for EOS. However, our center is the most common pediatric provider for babies born at UTMB, due to the characteristics of the population we serve.

Conclusions

In our population, we chose to monitor clinical status and CBC indices in neonates exposed to MC to avoid NICU access, prolonged length of stay, separation from mothers, and antibiotics in a big group of neonates who would prove to be healthy. CBC indices should not be used alone to predict the risk of EOS. This study adds evidence to support the apply of ascertainment-based approaches for managing newborns exposed to maternal chorioamnionitis. Using clinical observation and laboratory evaluation, nosotros were able to avert these agin events in 87% (239/275) of neonates exposed to MC. Our follow up data from neonates afterwards belch attests to the safety of observation-based approach for the management of maternal chorioamnionitis. Although this study is comparatively powered to assure complete elimination of EOS, the current recommendations for close follow-upwards after discharge is a useful prophylactic cyberspace.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current report are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable asking.

Abbreviations

- AAP:

-

American Academy of Pediatrics

- ACOG:

-

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- ANC:

-

absolute neutrophil count

- CBC:

-

complete blood cell count

- CDC:

-

Eye for Illness Command and Prevention

- EOS:

-

early on-onset sepsis

- GA:

-

gestational age

- GBS:

-

Group B Streptococcus

- HOL:

-

hours of life

- MC:

-

maternal chorioamnionitis

- NICU:

-

neonatal intensive care unit

- ROM:

-

rupture of membrane

- TLC:

-

full leukocyte count

- UTMB:

-

University of Texas Medical Co-operative

References

-

Yancey MK, Duff P, Kubilis P, Clark P, Frentzen BH. Risk factors for neonatal sepsis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):188–94.

-

Adams WG, Kinney JS, Schuchat A, Collier CL, Papasian CJ, Kilbride HW, Riedo FX, Broome CV. Outbreak of early onset group B streptococcal sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12(seven):565–70.

-

Malloy MH. Chorioamnionitis: epidemiology of newborn management and consequence United States 2008. J Perinatol. 2014;34(8):611–5.

-

Benitz WE, Wynn JL, Polin RA. Reappraisal of guidelines for management of neonates with suspected early-onset sepsis. J Pediatr. 2015;166(4):1070–4.

-

Higgins RD, Saade G, Polin RA, Grobman WA, Buhimschi IA, Watterberg K, Silverish RM, Raju TN. Evaluation and Direction of Women and Newborns with a maternal diagnosis of Chorioamnionitis: summary of a workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(three):426–36.

-

Commission Stance No. 712: Intrapartum Management of Intraamniotic Infection. Obstet Gynecol 2017, 130(2):e95-e101.

-

Puopolo KM, Benitz WE, Zaoutis TE. Management of Neonates Born at >/=35 0/7 Weeks' gestation with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial Sepsis. Pediatrics. 2018.

-

Carola D, Vasconcellos M, Sloane A, McElwee D, Edwards C, Greenspan J, Aghai ZH. Utility of early-onset Sepsis risk calculator for neonates born to mothers with Chorioamnionitis. J Pediatr. 2018;195:48–52 e41.

-

Ayrapetyan Thousand, Carola D, Lakshminrusimha S, Bhandari V, Aghai ZH. Infants built-in to mothers with clinical Chorioamnionitis: a cantankerous-sectional survey on the use of early-onset Sepsis take chances figurer and prolonged use of antibiotics. Am J Perinatol. 2018.

-

Jan AI, Ramanathan R, Cayabyab RG. Chorioamnionitis and Management of Asymptomatic Infants >/=35 weeks without empiric antibiotics. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1).

-

Money North, Newman J, Demissie S, Roth P, Blau J. Anti-microbial stewardship: antibiotic use in well-appearing term neonates born to mothers with chorioamnionitis. J Perinatol. 2017;37(12):1304–9.

-

Gibbs RS, Blanco JD, St Clair PJ, Castaneda YS. Quantitative bacteriology of amniotic fluid from women with clinical intraamniotic infection at term. J Infect Dis. 1982;145(1):1–viii.

-

Avila C, Willins JL, Jackson M, Mathai J, Jabsky M, Kong A, Callaghan F, Ishkin Due south, Shroyer AL. Usefulness of two clinical chorioamnionitis definitions in predicting neonatal infectious outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(11):1001–9.

-

Hooven TA, Randis TM, Polin RA. What's the harm? Risks and benefits of evolving rule-out sepsis practices. J Perinatol. 2018;38(6):614–22.

-

Verani JR, McGee 50, Schrag SJ. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal affliction--revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and bloodshed weekly report Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control. 2010, 59:Rr–ten):one-36.

-

Polin RA. Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):1006–15.

-

Weston EJ, Pondo T, Lewis MM, Martell-Cleary P, Morin C, Jewell B, Daily P, Apostol Thousand, Petit Due south, Farley M, et al. The burden of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States, 2005-2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;xxx(xi):937–41.

-

Alexander JM, McIntire DM, Leveno KJ. Chorioamnionitis and the prognosis for term infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(2):274–8.

-

Kiser C, Nawab U, McKenna Grand, Aghai ZH. Role of guidelines on length of therapy in chorioamnionitis and neonatal sepsis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):992–8.

-

Wortham JM, Hansen NI, Schrag SJ, Hale E, Van Meurs G, Sanchez PJ, Cantey JB, Faix R, Poindexter B, Goldberg R, et al. Chorioamnionitis and civilization-confirmed, early-onset neonatal infections. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1).

-

Puopolo KM, Draper D, Wi Southward, Newman TB, Zupancic J, Lieberman E, Smith K, Escobar GJ. Estimating the probability of neonatal early-onset infection on the basis of maternal run a risk factors. Pediatrics. 2011;128(five):e1155–63.

-

Escobar GJ, Puopolo KM, Wi S, Turk BJ, Kuzniewicz MW, Walsh EM, Newman TB, Zupancic J, Lieberman E, Draper D. Stratification of risk of early-onset Sepsis in newborns ≥34 weeks' gestation. Pediatrics. 2014;133(one):30–6.

-

Kuzniewicz MW, Puopolo KM, Fischer A, Walsh EM, Li S, Newman TB, Kipnis P, Escobar GJ. A quantitative, adventure-based approach to the direction of neonatal early-onset Sepsis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):365–71.

-

Smulian JC, Bhandari V, Vintzileos AM, Shen-Schwarz S, Quashie C, Lai-Lin YL, Ananth CV. Intrapartum fever at term: serum and histologic markers of inflammation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(i):269–74.

-

Hornik CP, Benjamin DK, Becker KC, Benjamin DK, Li J, Clark RH, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Smith Lead. Use of the complete claret cell count in early-onset neonatal Sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(viii):799–802.

-

Newman TB, Puopolo KM, Wi Southward, Draper D, Escobar GJ. Interpreting consummate blood counts soon after birth in newborns at risk for sepsis. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):903–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No external funding.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

MS conceptualized and designed the written report, nerveless the information, carried out the statistical analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. MFF assisted with information collection, statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. KS conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised information collection, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the concluding manuscript as submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Academy of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, approved the report. The need for written consent was waived by the IRB.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided yous give appropriate credit to the original writer(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zippo/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Sahni, M., Franco-Fuenmayor, M.E. & Shattuck, K. Management of Late Preterm and Term Neonates exposed to maternal Chorioamnionitis. BMC Pediatr 19, 282 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1650-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12887-019-1650-0

Keywords

- CBC

- Newborn

- Sepsis

- Antibiotics

Source: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-019-1650-0

0 Response to "What to Give Baby if They Have Chorioamnionitis"

ارسال یک نظر